By Arthur Potatoehammer

The “Greater Idaho Project” is a political movement that advocates for the secession of several rural counties in Eastern Oregon to join the state of Idaho.

This initiative stems from a significant cultural and political divide between Oregon’s rural and urban areas, particularly between the conservative-leaning eastern region and the more liberal, urbanized western part of the state.

Origins and Motivation

The project arose from frustrations among many residents of Eastern Oregon who feel that their values, interests, and needs are not adequately represented by the state government, which is dominated by politicians from the more populous and progressive cities like Portland and Eugene.

These rural Oregonians are generally more conservative, particularly on issues such as gun rights, taxation, environmental regulations, and land use.

They argue that the policies enacted by the state legislature reflect urban priorities, which they see as out of touch with their way of life.

The Greater Idaho movement proposes that these rural counties would be better served by joining Idaho, a state with more conservative governance and policies that align more closely with their values.

The project has gained momentum through grassroots campaigns, with several counties in Oregon voting in favor of exploring the possibility of joining Idaho.

The movement has employed petitions, ballot measures, and local referenda to advance their cause.

The Proposal

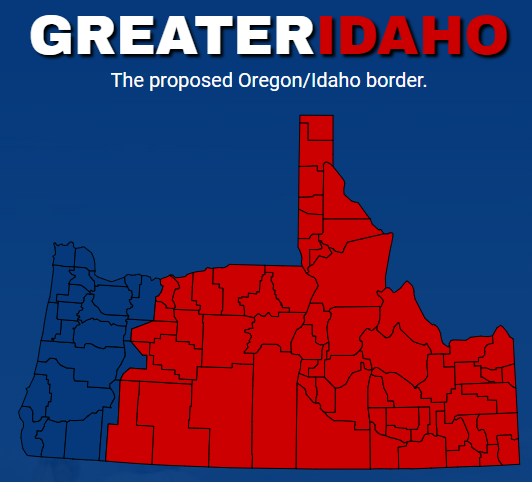

The concept involves redrawing state boundaries so that a significant portion of Oregon’s landmass—though not its population—would become part of Idaho.

This would include over a dozen counties in Oregon, as well as parts of Northern California, potentially shifting into Idaho’s jurisdiction.

Proponents argue that this change would allow residents of these areas to live under a government more attuned to their beliefs and needs.

Political and Legal Challenges

However, the Greater Idaho Project faces significant political and legal obstacles.

Changing state boundaries requires the approval of both state legislatures involved (Oregon and Idaho in this case) and the U.S. Congress.

The Oregon legislature, which is dominated by Democrats, is unlikely to approve such a move, as it would reduce the state’s population and tax base, while Idaho’s legislature might be more receptive due to the potential for increased land and political influence.

Opponents of the project also argue that it could lead to negative economic consequences, such as disruptions in public services, changes in tax structures, and complications in existing state-funded programs.

Additionally, critics view the movement as a form of political gerrymandering on a grand scale, driven by ideological dissatisfaction rather than genuine logistical or economic concerns.

Current Status and Impact

As of now, the Greater Idaho Project remains in the preliminary stages of local referenda and discussions.

However, it has sparked a significant debate about state governance, representation, and the cultural divide between urban and rural America.

The movement, regardless of its success, underscores the deep-seated regional differences within states and the ongoing challenges of balancing diverse political interests within a single state’s borders.

In summary, the Greater Idaho Project represents a unique response to political and cultural dissatisfaction, highlighting broader tensions in American federalism and the complexities of state and regional identity.

This is content of a recent email I received from the “Greater Idaho Project” I follow it as I originally came from that region:

The leadership team of Greater Idaho is coming to your county! Over the next several months, we will be hosting weekly Townhalls in eastern Oregon counties who have passed our measures. If you want to know what’s happening with moving the border and how you can help move us forward, please plan on attending. In addition, we plan on inviting all county commissioners and elected representatives and senators. This would be a great time to ask them what they are doing to advocate for moving the border and encourage them to do more to get voters’ goals achieved.

Check out when we’ll be in your county!

A month ago Greater Idaho reached out to the Governor’s office and formally invited her to meet with our team – anytime, anywhere. We have yet to hear back from her or her staff. It is clear to us that the Governor is not interested in hearing out her constituents so we need you, the people she represents, to reach out and let her know that you want to explore moving our border!

Contact the Governor Here

Many of you answered the call in our last newsletter to begin making a monthly donation towards moving the border. Thank-you! Please join those who’ve already made a commitment and consider signing up for a recurring donation. Just $10 or $20 dollars a month can make a huge impact in our ability to get the legislation we need through the Oregon and Idaho Legislatures, and could be the best long-term investment in your family’s future you’ve ever made!

Last week, Crook County Commissioners became the 8th board of commissioners to formally ask for legislative action on moving the border. This is exactly how the system is supposed to work! Reach out and let them know you appreciate their advocacy, and be sure to also reach out to your state representative and senator and let them know you expect them to do the same.

Contact Your Elected Representatives by Clicking on Your County Here

How did Oregon’s border end up where it is anyways? Alicia Zinni did some research and what she discovered may surprise you.

In 1846, Oregon became a territory, sandwiched between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountain crest to the east. Counties had been forming within the western portion of the territory, and by 1854, there were 18 counties west of the Cascades while everything east of

the Cascades was named Wasco County. It was the largest county ever formed in the United States at 130,000 square miles. Wasco County was the parent from which parts of Idaho and Wyoming were split. It was also the parent from which 17 eastern Oregon counties split. Wasco county is now only 2395 square miles in size.

A territorial legislature had been governing the area, formed by each county sending representatives to the House and Council (now senate). By 1857 the legislature had decided to approach Congress with proposed statehood, which meant recommending a state boundary. A special committee of the legislature met in August of 1857 to determine the best state line.

In this debate, we hear from:

• James Kelly of Clackamas County and Council President

• Thomas Dryer of Multnomah and Clackamas counties

• Mr. Smith who was either from Lane and Benton counties or from Linn County,

• La Fayette Grover of Marion County and House Speaker, and

• Charles Meigs, the lonely voice for the 130,000-square-mile Wasco County.

The group was entertaining a proposed motion for the Snake and Owyhee rivers as the east state boundary. Charles Meigs then moved for an amendment to make the Cascades the eastern boundary instead, leaving parts east of the Cascades as a territory.

The following reporting on the debate is excerpted from The Oregon Statesman’s September 1, 1857 edition.

Mr. Meigs moved to amend so as to make the Eastern boundary range on or near the summit of the Cascade range, leaving the Dalles out of the State.

Mr. Dryer was opposed to the amendment. He was opposed to a small State. He was in favor of taking in the Territory east of the Cascade. If we are going to have a State, let us have a large one – we have land enough. There were some people at the Dalles in favor of a new Territory, but he never heard any reason given for it. He was in favor of going to Missouri and taking in Utah if we could.

Mr. Smith . . . saw no good purpose to be promoted by adopting this motion. He could see no motive the people of Wasco County could have for desiring it to be done. The Dalles was a gate through which the people and merchandise of both sides of the Cascades must pass through. The only argument he had heard, was that small states would give us more senators – that was true, but when would we have them. He regretted that Washington Territory had been cut off, and had we it now, he would be in favor of the Cascades as our eastern boundary. He had pride of State and pride of country; he liked large States and large countries, and he thanked God that he belonged to one – a powerful one, that commanded the respect and excited the fear of the other nations of the world. It was true small states had as many votes as large ones, but they had nothing like as much influence. If a constitution was to be submitted with the Cascades as a boundary, it would not get votes enough to make a shirt collar.

Mr. Grover said we had more wasteland proportionately and less arable land than the other States of the Union. If we were to make the Cascades the boundary, we should have about the same amount of arable land [as] New Jersey, which ranks as one of the small States of the Union had. He said it was the desire of the citizens living in the portion of Washington included in the boundary, that the Cascades should be the boundary, but if it was not, they preferred the

boundary named in the report. It was not improbable that at some day not distant, the Dalles would be the seat of government of Oregon. Its position was likely to be more central to the future State of Oregon than say other.

Mr. Meigs said he had expected others than himself would have supported the Cascades boundary, but it seemed he stood alone in support of it. That the Cascades should be our eastern boundary was a self evident proposition. It was a maxim of political science that great natural boundaries should be observed in the organization

of States and governments. The Cascades constituted such a boundary. There were but three known trails over those mountains and those trails were impassible for six or eight months of

the year. It was entirely gratuitous to presume that the interests of the people east of the Cascades would be promoted by being attached to Oregon. They understood the question, and were united in the opinion that they would be bettered by separation. He tho’t the Territory east of the Cascades would make a sufficiently large State – that it would contain much more arable land than Mr. Grover supposed.

He believed there was land enough vacant west of the Cascades for all such purposes. It had been said that if the Cascades was made the boundary, the people west of those mountains would be left in a state of vassalage. The people there preferred to be in a state of Vassalage to the United States than to this part of Oregon.

The amendment of Mr. Meigs was lost.

So there you go. Some things never change. As far back as 1857, eastern Oregon representatives were overturned by a western Oregon power block looking to maximize their wealth and gain. Thank you Mr. Charles Meigs for your effort. The Greater Idaho movement is

picking up where you left off.

greateridaho.org

Twitter