According to today’s report from the federal government’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, the US economy added 227,000 payroll jobs during November, according to the establishment survey. The unemployment rate rose slightly to 4.2 percent.

This follows October’s jobs report which was the weakest since 2020. In October, private-sector employment fell month-over-month by 2,000 jobs.

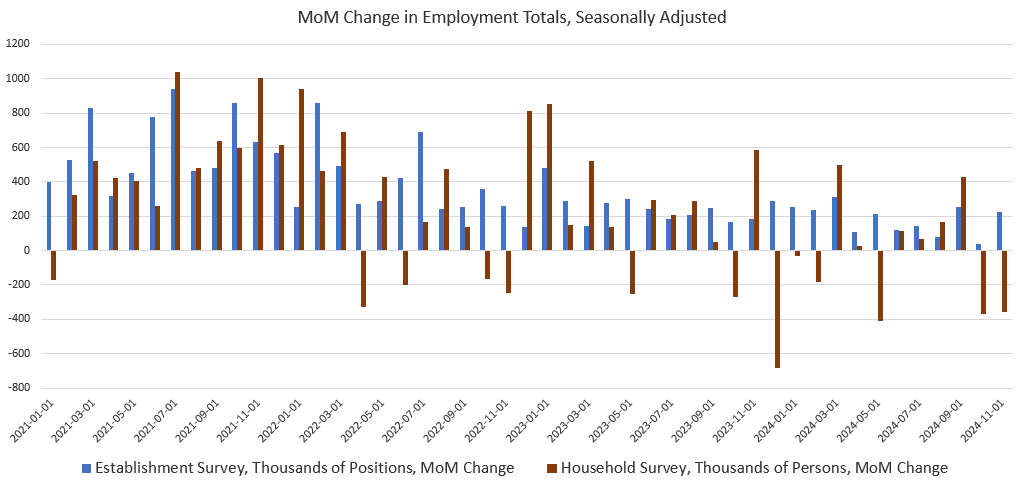

So, many media outlets described this latest report as a “rebound” or sorts from October’s weak numbers. Unfortunately, if we look beyond the headline establishment survey number, we don’t find much evidence of a rebound at all.

According to the BLS’s other survey, the household survey, we find that the total number of employed workers fell for the second month in a row in November, and that full-time jobs have collapsed over the past year.

The establishment survey is a survey of large employers and is a measure of jobs—both part-time and full-time—but not of actual workers. The household survey, on the other hand, measures employed workers and gives us data on full-time and part-time work.

So, when we combine both surveys, we can end up with a picture of an economy that has added many jobs, but not necessarily many employed persons if new work is largely part time.

That appears to be what is going on right now. While the establishment survey shows a gain of 227,000 jobs from October to November, the number of employed workers fell by 355,000 jobs during the same period.

A similar dichotomy shows up in the year-over-year change. From November 2023 to November of this year, the total number of jobs grew by 2.2 million, according to the establishment survey. The household survey, on the other hand, shows a loss of 725,000 workers over the same period.

Moreover, total workers in the household survey has been flat for nearly eighteen months. As of November, there were 161,100 employed workers. That’s about equal to June 2023. Indeed, total employed workers has generally moved sideways for almost two years.

The lack of growth in the employed workforce is at least partly explained by the growing importance of part time work in the economy. In November, both full time and part-time work fell, month-over-month for the second month in a row. Part-time work fell by 268,000 from October to November, while full-time work fell by 111,000 during the same period.

Year-over-year, though, the drop in full-time work has been much larger. From November 2023 to November of this year, full-time work fell by 1.3 million, while part-time work rose by 634,000. In other words, the job growth we are seeing out there is primarily part-time work.

Persistent drops in full-time work have been an indicator of an impending recession for at least 50 years. Whenever year over year full-time work has gone negative for three months or more, the US has either been in recession or approaching a recession. As of November, full-time employment has been down, year over year, for ten months in a row.

Perhaps now that the election is over, and Biden is defeated, the media and administration appear to be less committed to claiming that every uptick in the establishment survey suggests the economy is soaring to new heights. Rather, the Fed response to the November report was largely to declare that the data is “promising” but that the Fed will not be deterred from its efforts to force down interest rates even more in coming months.

Forcing down interest rates, of course, has been the Fed’s clearly stated goal since late summer, and the Fed kicked off the current loosening cycle with a mega-cut of 50 basis points in September. This was followed by a second cut of 25 basis points last month. The rosy numbers coming out of the establishment survey—October’s report excluded, of course—have not been enough to dissuade the Fed from further opening the easy-money spigots.

What Fed Policy Might Be Telling US

There are at least two options for why this is. The first option is that the Fed knows the current state of the US economy isn’t nearly as good as is suggested by a myriad of Fed press releases and spokespeople. After all, if the economy truly is strong, the Fed’s oversized 50 basis-point cut in September is inexplicable. Even if we consider the theory that the Fed cut the target rate to give candidate Kamala a boost, we’re still left wondering why a “historically strong” economy—as the administration’s rhetoric insisted was the case at the time—would need a “boost” at all. But, the fact that the Fed did cut in September, and then again in November, suggests ongoing concerns with the strength of the labor market.

Economic weakness is further suggested by Bloomberg economic Anna Wong who recently contradicted the administration’s claim that October’s weak jobs report was caused by striking workers and local economic damage caused by Hurrican Milton. Rather, as Wong points out, even if we remove the hurricane- and strike-battered states from the equation, the jobs situation was very weak indeed in October. Wong concludes: “something else is going on last month other than storms and strikes.”

In other words, October’s slide in jobs has never been explained, and there are likely deeper-seated issues here that have yet to be addressed or acknowledged.

Suspicions about the state of the economy are also showing up in the bond markets. Once today’s new data was released, and the Fed’s plans to keep cutting rates confirmed as a likely outcome, the yield on the 10-year treasury fell throughout the day. Bond investors may be gaining confidence that the Fed does indeed plan to cut the target rate again in the near future. Although longer-term bond yields trended upward throughout November on expectations of growing federal debts, recent falls in yields may suggest that bond investors now expect the Fed to really push down interest rates in pursuit of more economic stimulus.

This is understandable since we’ve heard very little from the Fed lately on the matter of price inflation. Fed personnel like Powell now appear to be treating the price inflation issue as if it’s ancient history. The Fed’s stated confidence on the price inflation front has been contradicted by the recent price index data, however. Three measure of price inflation closely watched by the Fed—CPI, core CPI, and “sticky” core CPI—all accelerated again in October.

Regardless of what the CPI data says, it may very well be that political worries about price inflation will have to take a back seat at the Fed because the Treasury needs the Fed to step in and force down interest rates to keep the federal government’s mounting deficits manageable. After all, with quarterly interest payments on the national debt now reaching north of a trillion dollars, debt service will consume the federal budget unless the Fed intervenes to force down interest rates. History has shown that the Fed has always intervened in this way when “asked,” and its safe bet the Fed and the Treasury are already focusing on debt management as a significant political problem.

A third option, of course, is that the Fed is motivated by both a desire to simulate employment and to drive down federal debt costs. The down side will be that regardless of motivation, a continued pursuit of easy money (i.e., artificially lowered interest rates) will lead to more price inflation and asset inflation. Those who don’t already own many assets, and those with fixed incomes and lower incomes will then face some serious affordability problems.

Originally Posted at https://mises.org/