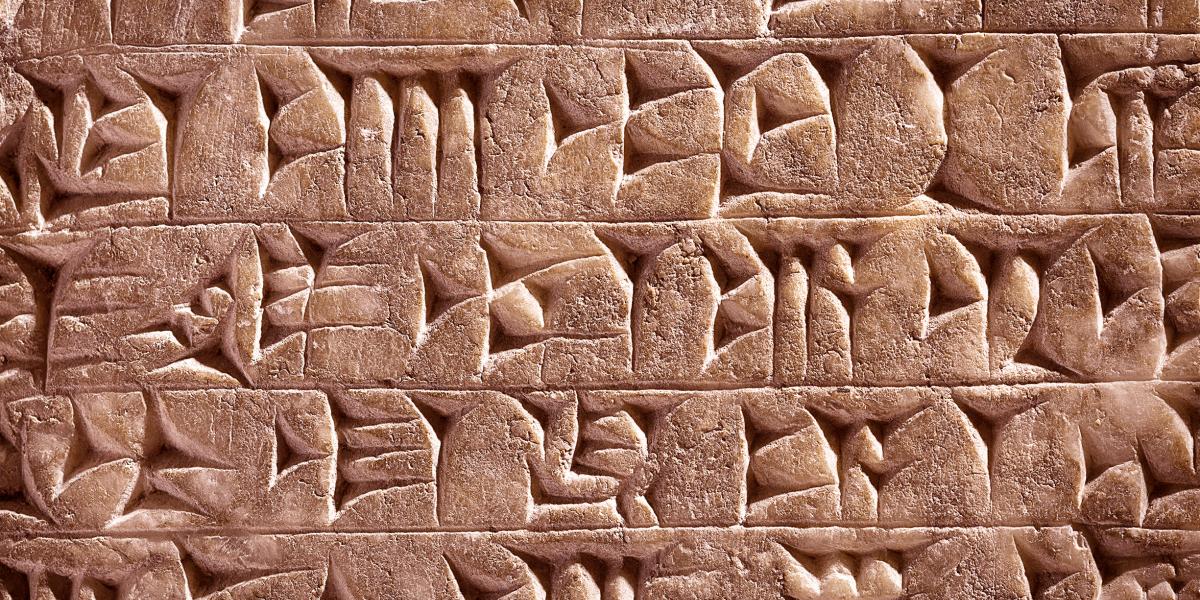

Principles of market economics, particularly those emphasized in Austrian economic thought, are not confined to modern systems but persist across epochs. Ancient narratives, such as Mesopotamian epics, reflect profound insights into human decision-making, resource allocation, and the dynamics of power and exchange. I have become fascinated by deciphering the economic principles embedded within and underlying these ancient texts. One such story, The Poor Man of Nippur, dating back to the Kassite period (ca. 1595-1155 BCE), offers timeless lessons about economic behavior through the lens of Gimil-Ninurta’s struggles and triumphs.

Set in the city of Nippur—a religious and administrative hub—the tale follows Gimil-Ninurta, a destitute man seeking a way to escape his poverty and humiliation. This story circulated widely in folklore, appearing in various versions throughout the Middle East and beyond. It portrays an ancient hierarchical society organized as a state governed by the king and local authorities. The main motif is the revenge of a poor man who outwits the city’s mayor, who had wronged him. As in many folktales, justice prevails as evil is punished and the virtuous ultimately succeeds.

The epic describes Gimil-Ninurta as an unfortunate man, so poor that, “Every day, for want of a meal, he went to sleep hungry. He wore a garment for which there was none to change” (lines 9-10). Despite his poverty, he was not a slave but a free citizen having a house and a yard. To improve his situation, Gimil-Ninurta decides to trade his only possession—a garment—for a three-year-old nanny goat. This trade reveals his resourcefulness and skill as a shrewd negotiator: he managed to exchange worn clothing for a productive animal. At this point in the story, I assumed Gimil-Ninurta intended to start a herd. However, the plot soon proved more engaging and unpredictable.

His decision to buy the goat and his efforts to profit from it represent the central economic dilemma of the story. The text explains:

He debated with his wretched self, “What if I slaughter the nanny goat in my yard? There won’t be a meal, where will be the beer? My friends in my neighborhood will hear of it and be angry, my kith and kin will be furious with me. I’ll take the nanny goat and bring it to the mayor’s house. I’ll work up something good and fine for his appetite.” (lines 17-22)

Gimil-Ninurta’s purchase of the goat shows his understanding of the value of investing in a resource that can serve multiple purposes. A three-year-old female goat—at peak productivity for milk or breeding—was a deliberate and calculated acquisition. Despite his poverty, Gimil-Ninurta exercises economic agency, using his limited resources wisely and strategically.

Initially, he contemplates slaughtering the goat for an immediate meal. However, he quickly realizes this would provide only temporary satisfaction while damaging his relationships with neighbors and kin. In Mesopotamian culture, feasts were significant communal events, often involving both food and drink. A meal without beer would reflect poorly on the host and diminish their social standing. Recognizing this, Gimil-Ninurta decides to offer the goat to someone in power—the mayor.

Gimil-Ninurta understands that the mayor has influence and resources that could benefit him. By appealing to the mayor’s “appetite” and providing a fine gift, he hopes to secure favor or gain something of greater value in return, whether tangible (wealth, employment) or intangible (recognition, protection). The reciprocity of gifts was widely spread and the traditional way of behavior in ancient times. Thus, instead of being engaged in herding, which will take a considerable time, he explored this peculiar feature of ancient socio-economic relations.

This decision highlights the protagonist’s internal struggle between consuming the goat for immediate sustenance and using it as a gift, hoping to improve his circumstances. It reflects an economic subtext, mirroring the classic dilemma of whether to prioritize immediate consumption or defer gratification for potentially greater future rewards. By sacrificing the goat as a gift, Gimil-Ninurta chooses the latter, aiming to leverage his limited resources. However, his plan backfires when the mayor mocks him and offers only scraps in return: “To the doorman, who minded the gate, he said (these) words: ‘Give him, the citizen of Nippur, a bone and gristle, give him third-rate [beer] to drink from your flask, chase him away and throw him out the gate’” (lines 57-60)!

This act of injustice triggers Gimil-Ninurta’s clever revenge, where his wit and resilience lead to a reversal of fortunes. Devastated but undeterred, Gimil-Ninurta devises an audacious plan. He appears before the king with a bold business proposition, asking to borrow the royal chariot for one day in exchange for a payment of one mina of red gold—a weight of approximately 500 grams, worth around $41,478 in today’s gold prices. Comparatively, renting a carriage in New York’s Central Park costs about $150 per hour or $2,400 per day. Thus, the king would earn a profit of $39,078 in today’s prices for lending his carriage for one day, resulting in a staggering 1,628.25 percent profit margin. While modern investors might balk at such an implausible offer, the king, understanding the symbolic value of trust and risk, agrees—demonstrating why he is king.

With the royal chariot in hand, Gimil-Ninurta portrays himself as a noble official to the mayor, committing what could be described as “justifiable” fraud. He places two birds in a box and claims it contains two minas’ worth of gold, destined for the temple. That night, he secretly releases the birds. By morning, the empty box creates a scandal. The mayor—fearing accusations of theft or negligence—compensates Gimil-Ninurta for the supposed loss with two minas of gold. Through this scheme, Gimil-Ninurta not only recovers more than he had initially lost but also exposes the mayor’s greed and gullibility.

The act of fraud, though deceptive, is portrayed in the story as a form of poetic justice, reflecting a broader theme of balance and retribution in Mesopotamian literature. His wit and ingenuity allowed him to achieve both personal redemption and a symbolic triumph over those in power. He punished the mayor two more times as he promised, but rather physically and morally rather than economically.

From an economic perspective, Gimil-Ninurta’s actions closely align with Austrian economic principles, particularly time preference—the trade-off between present consumption and future consumption. By deferring gratification and risking his last resources, Gimil-Ninurta exemplifies a low time preference—sacrificing immediate needs to achieve long-term goals. Slaughtering the goat for food would provide immediate satisfaction but no lasting benefit. Austrian economics also emphasizes opportunity cost, as seen in Gimil-Ninurta’s decision to forgo consuming the goat in favor of a speculative return. His entrepreneurial spirit, creativity, and ability to bear risks embody the Austrian model of resource allocation and innovation (while not excusing the ethical issue of fraud).

The story also implicitly critiques inefficiencies in hierarchical societies, where power imbalances distort fair exchanges. The mayor’s and the king’s involvement in economic affairs mirrors Austrian critiques of state interventions, which hinder free markets and perpetuate inequality by choosing winners and losers in the economic sphere. Thus, the state representative—the mayor—made Gimil-Ninurta lose, but the king helped him win. Ultimately, Gimil-Ninurta’s ingenuity restores fairness, showcasing the resilience required to navigate unjust systems.

The theme of trust, credibility, and reputation also runs through the plot of the story and is reflected in modern business folklore. There is a contemporary parable about a young proprietor who asked for an appointment with a financial tycoon. The tycoon agreed to meet him, but only while walking from his office to his car. The entrepreneur gladly accepted the offer, and they walked together. “Why are you silent?” asked the tycoon. “I got what I need,” replied the businessman. “Now I can get any credit line I want because people have seen me with you.”

The parable of the young investor and the story of Gimil-Ninurta align through their shared emphasis on leveraging association with powerful figures to achieve significant economic or social gains. In both tales, the heroes transform a symbolic connection —walking with a tycoon or using the king’s chariot—into a tool for building credibility and influence. The businessman gains access to credit simply by being seen with the tycoon, while Gimil-Ninurta uses the royal carriage to establish himself as a figure of authority, compelling the mayor to compensate him. These stories underscore the value of social capital and reputation, where perception holds as much weight as tangible assets. Both narratives highlight entrepreneurial initiative, showcasing how individuals can exploit hierarchical systems to their advantage by maneuvering appearances and leveraging trust.

The lessons of The Poor Man of Nippur transcend its historical and cultural context. Its economic insights reflect the universal challenges of managing scarce resources, navigating power dynamics, and pursuing long-term goals. The tale’s resonance with Austrian economics underscores that market principles are forces within society, deeply rooted in the timeless human struggle to choose between satisfying present desires and striving for future aspirations.

Originally Posted at https://mises.org/