Economists have long sought to integrate the subject matter of money into the general theory of the market. Various monetary doctrines and theories have been formulated to achieve this aim. However, most of them were refuted on the basis of inherent flaws in the arguments and/or conclusions. One of the standing theories of money is the quantity theory.

The old quantity theory of money proved helpful in providing the insight that the exchange-ratio between money and the various vendible goods and services can be determined in the same manner in which the mutual exchange-ratios between the various commodities are determined: by demand and supply. It essentially integrated the special instance of money into the broader theory of demand and supply.

However, the old quantity theory of money, by adopting a holistic approach in its analysis of money, ignored the various degrees to which changes in the money supply affected the money-prices of the various commodities and other related market phenomena. Attempts were made to restate the quantity theory in mathematical terms, but this resulted in fallacious deductions that abstracted human action out of the picture. Mises puts it as follows in Human Action:

In order to prove the doctrine that the quantity of money and prices rise and fall proportionately, recourse was had in dealing with the theory of money to a procedure entirely different from that modern economics applies in dealing with all its problems.

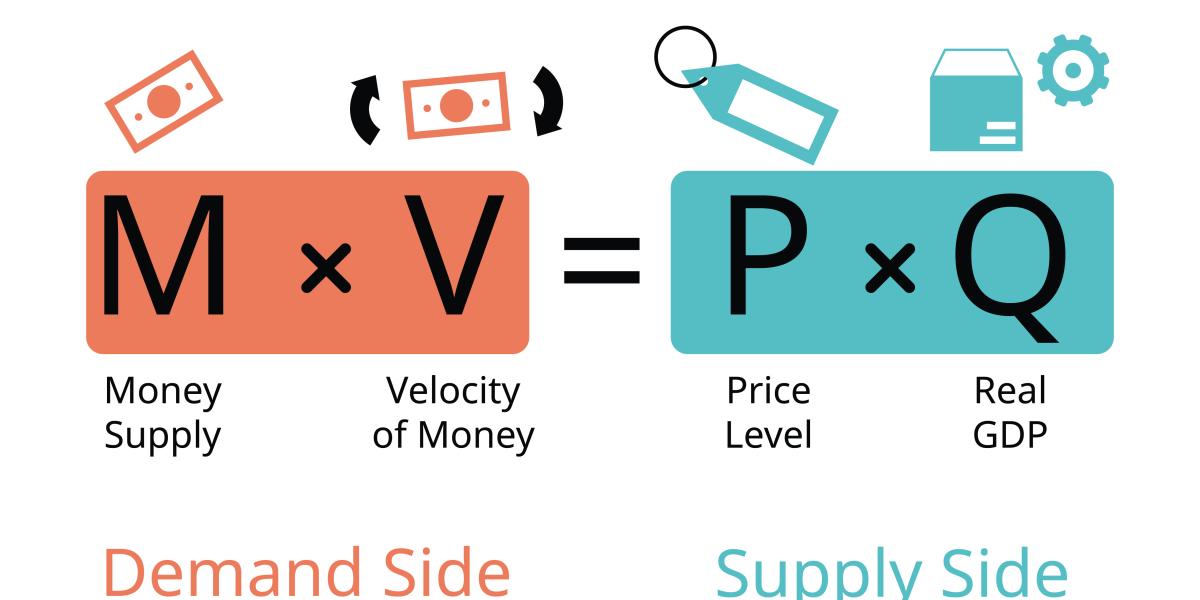

One of such procedures is the mathematical economists’ recourse to the “equation of exchange,” formulated by Irving Fisher in 1911. The equation of exchange attempts to establish a mathematical relationship between changes in the money stock and the so-called “general price level” of commodities. The equation of exchange asserts that MV = PQ; it comprises such aggregates as total supply of money (M), a mechanistic component so-called “velocity of circulation of the monetary unit” (V), volume of trade (Q), and general price level (P). The identity implied in this equation led to the erroneous notion of neutrality of money, which asserts that changing the total quantity of money in circulation (M) would lead to a proportionate change in the price level (P) of the various commodities, all other factors being constant.

Critique of the Components of the Equation of Exchange

The so-called “price level” (P), however, is not a meaningful concept in praxeology. In the real world of action, time, and choice, nowhere do we find a uniform “level” for all prices; rather, at any given time, what we find is an array of historical prices established by individuals under given conditions that are unique and non-repeatable. Moreover, changes in money supply can only affect prices by way of subjective valuations of buyers and sellers.

In addition, when acting men embark upon indirect exchange, they do not consider the total output or “volume of trade” (Q), they are only conscious of definite quantities of a commodity, which they value more in relation to definite quantities of another commodity, which they value less. This has also been the procedure of sound economic theory in analyzing human action.

The “velocity of money” (V)—another component of the equation of exchange—is merely an arbitrary import from mechanics and physics. Every unit of the total stock of money in an economy constitutes the cash holding of specific members of the community. Consequently, each individual spends his money at different times and to different extents according to his subjective valuations. There is no uniform frequency of spending in the economy. Therefore, the assignment of any magnitude depicting “velocity of money” is arbitrary.

Hence, from a categorical rejection of the holistic approach and arbitrariness of components of the equation of exchange, we proceed to reestablish the following facts based on the methodological individualism of praxeology:

The first is that changes in money relations do not apply to the economy as an entity independent of the actions of individuals. Rather, these changes affect the particular cash balances of various individuals whose actions and reactions constitute the economy. Aggregates are only meaningful insofar as they do not overlook the specific changes that occur at the individual level. Given that an increase or decrease in the money supply cannot be effected otherwise than by a reduction or increase in the cash holdings of individuals, any procedure precluding actions of individuals in favor of the “whole” would ultimately lead to fallacious conclusions. Mises, writing in Human Action, highlighted the methodological error of the mathematical economists as follows: “Instead of starting from the actions of individuals, as catallactics must do without exception, formulas were constructed designed to comprehend the whole of the market economy.”

The second fact that must be established is that changes in the total stock of money do not affect the money prices of the various commodities at the same time and to the same extent. This invalidates the notion of even, proportional, and simultaneous changes in prices brought about by a change in money supply.

New money enters the economy through the spending of individuals on specific commodities. This increases the cash holdings of the sellers of these goods and services, which are bought by the recipients of the new money; the sellers proceed to acquire other commodities with the additional money in their possession, gradually driving up demand and prices of the goods in question. This process continues until the effect of the change in money supply extends to every commodity in the market.

The initial sellers who encounter these competitive buyers with extra spending power enjoy the benefit of price differentials between the commodities they sell and those they buy during the “transition period,” in which all prices are not yet affected by the change in money supply. The implication of the above social relations is that the prices of some goods rise as a result of the increase in money supply, while the prices of other commodities remain yet-to-be-affected by this change. Mises, in Human Action, explains the state of the economy under an increase in money supply as follows:

While the process is under way, some people enjoy the benefit of higher prices for the goods or services they sell, while the prices of the things they buy have not yet risen or have not risen to the same extent. On the other hand, there are people who are in the unhappy situation of selling commodities and services whose prices have not yet risen or not in the same degree as the prices of the goods they must buy for their daily consumption. For the former, the progressive rise in prices is a boon; for the latter, a calamity.

In conclusion, the equation of exchange does not correctly represent the money relations that take place in an economy. Its assumptions are unfounded, and its parameters do not convey meaningful economic knowledge. Mises’ succinctly summarizes as follows in Human Action:

The equation of exchange is incompatible with the fundamental principles of economic thought. It is a relapse to the thinking of ages in which people failed to comprehend praxeological phenomena because they were committed to holistic notions.

Originally Posted at https://mises.org/