New York Times’ ‘Distorted’ Coverage Of CCP Abuses Likely Cost Lives, Report Says

Authored by Petr Svab via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

At critical moments over the past 25 years, the New York Times has aided the interests of a power faction within the Chinese Communist Party responsible for atrocities against practitioners of the spiritual discipline Falun Gong.

On top of implicating itself ethically, the paper has also, as a result, distorted its China coverage and misled its readers, as revealed by an analysis of The New York Times’ China coverage as well as interviews with half a dozen experts on Chinese Communist Party (CCP) politics and geopolitics.

Due to the paper’s disproportionate influence on policy, its skewed coverage has likely led to a loss of life and treasure that is difficult to quantify, some experts said.

The New York Times has for decades positioned itself as a global newspaper, insisting on a necessity of access to China, according to former staffers. That meant convincing the communist regime that the paper’s presence would benefit it.

The paper has never explained what price it has paid for access to the country.

“There’s always the issue of, if you want to be a global newspaper, what do you have to do to keep China happy and stay in business there?” Tom Kuntz, a former editor at the paper, told The Epoch Times.

“There’s always been tensions, and I know they’ve, like a lot of companies, tried to maintain access to China.”

Bradley Thayer, a former senior fellow at the Center for Security Policy, expert on strategic assessment of China, and a contributor to The Epoch Times, was more blunt.

“If they don’t cover the regime the way the regime wants to be covered, they’re going to be blackballed. They’re not going to be able to return,” he told The Epoch Times.

“So all of these individuals have a vested interest, if you will, in toeing the Party line.”

Covering Chinese politics, The New York Times has ascribed sincerity where deception is expected and glossed over where it should have dug deeper, all in a pattern of affinity with the interests of a CCP clique aligned with former Party leader Jiang Zemin, multiple experts affirmed.

Jiang’s influence has waned since 2012, when incoming CCP leader Xi Jinping exhibited an unexpected dexterity in eliminating his opponents. Only a minority of Jiang’s acolytes have maintained influence since his death in 2022. Despite the shift in power, however, The New York Times has maintained the pro-Jiang pattern.

The New York Times did not respond to a detailed list of emailed questions for this article.

Privileged Position

The paper developed a special connection with Jiang in 2001, when its then-publisher, Arthur Sulzberger Jr., and several editors and reporters were granted a rare audience with the dictator.

The paper ran a flattering interview headlined “In Jiang’s Words: ‘I Hope the Western World Can Understand China Better.’”

Within days, the CCP unblocked access to The New York Times’ website in China.

A month later, the CCP unblocked several other Western news sites, including those of The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle, and the BBC. The sites were blocked again within a week.

The New York Times, on the other hand, remained accessible. Users then reported that content on the site was being blocked selectively, giving the paper a chance to benefit from access to the Chinese market to the degree that it kept within bounds acceptable to the CCP.

The interview came at a sensitive time for Jiang. He had only a little more than a year left before he was supposed to hand over Party control to Hu Jintao, fulfilling the succession line stipulated by Deng Xiaoping, his predecessor.

But things weren’t going well for Jiang. His persecution of the spiritual practice Falun Gong, a political campaign that was supposed to whip the Party and the nation into conformity under his control, was failing to reach its goals. Even worse, foreign media, including The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post, were taking apart the CCP’s anti-Falun Gong propaganda and highlighting accounts of wrongful detention and torture.

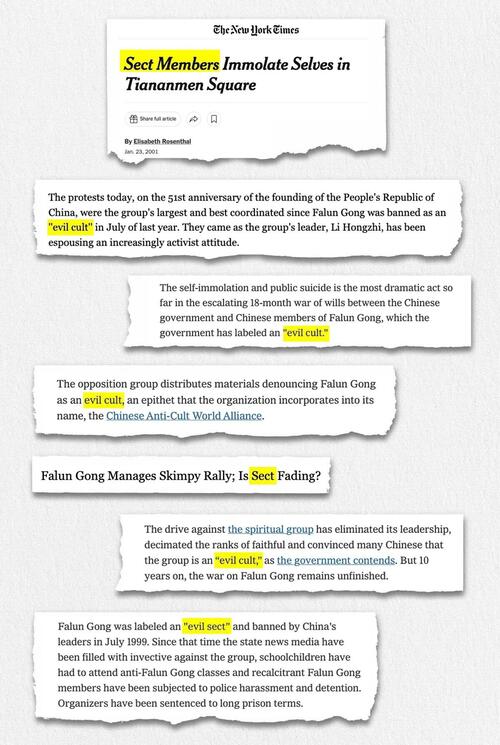

The New York Times, by contrast, appeared most helpful to Jiang’s campaign. By the time of the 2001 interview, the paper ran several dozen articles on Falun Gong, almost all of them profusely parroting the propaganda portraying the practice as a “cult” or a “sect.”

Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa, is a spiritual discipline consisting of slow-moving exercises and teachings based on the principles of truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance. It was introduced to the public in China in 1992, and by the end of the decade, an estimated 70 million to 100 million people were practicing it.

When in January 2001 CCP state media claimed that several people who set themselves on fire on Tiananmen Square in Beijing were Falun Gong practitioners, The Washington Post dispatched a reporter to fact-check the story. The New York Times, on the other hand, immediately took the CCP line as fact.

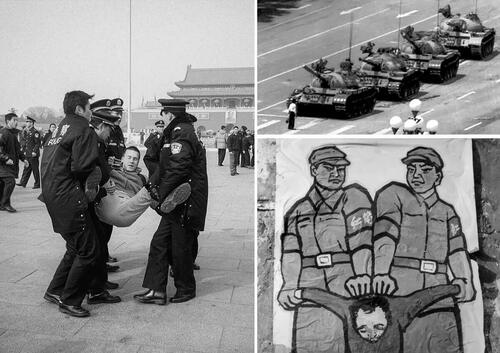

If the paper employed its much-touted investigative acumen, it would have discovered, as others have, that the incident was staged. After the first man allegedly set himself alight in the middle of the square, four policemen somehow managed to obtain several fire extinguishers, rush to the scene, and put out the fire, all in less than one minute.

Given the distances involved on the giant square, that wouldn’t have been physically possible—unless the officers already had the fire extinguishers ready and knew in advance where on the square they would be needed that day, several independent investigations concluded, pointing out dozens of other inconsistencies.

Even without any investigation, the incident made little sense. The victims supposedly followed a belief that burning themselves alive would bring them to heaven. But Falun Gong includes no such belief. In fact, its literature treats suicide as killing a human life, which it explicitly prohibits.

The New York Times didn’t even find it strange that since Falun Gong’s public introduction in 1992, of the tens of millions of people practicing it, none of them had publicly set themselves on fire until that day, and none had done so since.

Even after The Washington Post investigation traced several of the alleged victims back to their hometown and found that none had ever been seen practicing Falun Gong, The New York Times continued to parrot the CCP’s propaganda.

Jiang was apparently pleased with The New York Times, calling it during the 2001 interview “a very good paper.”

Getting in Jiang’s good graces on the Falun Gong issue would have been particularly critical, as it struck at the heart of a core principle of CCP politics, several experts affirmed.

Partners in Crime

One of the bedrocks of the CCP’s internal politics is ensuring one’s own safety, particularly upon retirement. Cadres are well aware of the pitiful fate of many high-ranking comrades. Infamously, Liu Shaoqi, once No. 2 to the CCP’s first leader, Mao Zedong, was purged during the Cultural Revolution, arrested, and tortured to death.

When Mao’s successor, Deng Xiaoping, looked for somebody to helm the CCP after him in 1989, he picked Jiang Zemin, the Shanghai Party secretary who supported the CCP’s deployment of military to crush the 1989 student protests.

“Because Jiang was implicated in the repression of the students, Deng could trust Jiang to be his successor. Jiang could not in the future use the massacre against Deng without implicating himself,” explained Matthew Little, a senior editor of The Epoch Times, in a 2012 analysis.

The persecution of Falun Gong played much the same role for Jiang, who encouraged his cronies to build “political capital” by backing the campaign. Some did so with fervor, escalating the persecution to a point of unspeakable barbarity, particularly in encouraging torture to force Falun Gong practitioners to renounce their faith, The Epoch Times previously reported.

These officials, tied by shared complicity in the atrocities, were at the core of Jiang’s power faction, sometimes called the “Shanghai gang.”

In exchange for their support, Jiang let the gang abuse their offices and plunder state-owned assets, setting the tone for a nationwide culture of corruption.

That culture served a dual purpose for Jiang. On one hand, it allowed him to buy supporters, especially in the 1990s, when he struggled to form a power base among CCP cadres, who generally saw him as incompetent, according to an unofficial biography of Jiang published by The Epoch Times.

On the other hand, he could eliminate his rivals in the name of “anti-corruption.”

But the sword of anti-corruption cuts both ways. As Xi later demonstrated, it could be applied selectively against the Jiang faction, too.

The bond through culpability in the Falun Gong repression was more solid. The crimes became so extensive that none of the culprits would have risked their revelation, some China experts said.

There was a problem, though: Jiang’s designated replacement, Hu Jintao, showed little enthusiasm for the Falun Gong campaign.

“Jiang tried to push Hu to persecute Falun Gong and found he was quite reluctant,” said Li Linyi, a China commentator, expert on CCP internal politics, and Epoch Times contributor.

“Their relationship started to deteriorate after that. Jiang just felt more and more concerned about Hu.”

Just as the CCP under Deng redressed some victims of the Cultural Revolution, Hu could, at least theoretically, redress Falun Gong, blame Jiang, and purge his faction.

In reality, this was unlikely to happen, Li said.

“There was a huge price for redressing the Cultural Revolution,” he said. “Not only did some top CCP leaders get purged, but the CCP admitted they made a big mistake. That is not good for them in order to hold power in China in the long term. The CCP is still criticized for what they did during the Cultural Revolution.”

CCP leaders would only backtrack on Falun Gong as a last resort, if they felt it would save the regime, he said.

That didn’t mean, however, that Hu and his supporters couldn’t use the Falun Gong issue to endanger Jiang and his faction in other ways. Indeed, there’s evidence that they have.

“All [Jiang’s] policies could have continued to be carried out by Hu Jintao, except this one. … The only thing Jiang Zemin worried about was the policy of persecuting Falun Gong,” said Heng He, a veteran China commentator with NTD, a sister outlet of The Epoch Times.

Jiang was thus extremely motivated to constrain Hu and prop up his own image, several experts confirmed.

The New York Times proved helpful in this pursuit.

Shoring Up a Dictator’s Legacy

By 2002, The New York Times was in pro-Jiang mode. Parroting the Party propaganda, the paper declared that Falun Gong had been successfully “crushed.”

Citing CCP sources, it suggested that Falun Gong was already passé and that it only ever had 2 million practitioners. It went as far as claiming that the figure cited by Falun Gong sources, 70 million, was baseless.

Yet a few years earlier, before the persecution began, multiple Western and Chinese media, including The Associated Press and The New York Times, provided figures of 70 million or 100 million, generally attributing them to estimates by the Chinese State Sports Administration, which had the best insight due to a massive survey of Falun Gong practitioners it conducted in the late 1990s.

Read more here…

Loading…

Originally Posted at; https://www.zerohedge.com//

Stay Updated with news.freeptomaineradio.com’s Daily Newsletter

Stay informed! Subscribe to our daily newsletter to receive updates on our latest blog posts directly in your inbox. Don’t let important information get buried by big tech.

Current subscribers: